Oh my ears, my beautiful ears!

The things I do for this blog! Its not all soft jazz and biscuits I can tell you.

Sometimes you have to suffer a bit, to put yourself through something that you otherwise might not do.

How else can I explain the fact that I've just sat through six whole records of wild, ear-busting, fuzz drenched, screaming, gut-bucket, primal, fuzzed out, no-holds-barred, crazed, derivative, unleashed, fuzz-monster, insane, guitar madness, grimy, gritty, fuzzy (have I already used that word?) Hendrixploitation. This music is so out there that at times it almost feels like free-jazz - there's a point and a melody but you don't always know it. My God, its the kind of music that can only be made by people who either want to break boundaries or who don't know that there are any boundaries in the first place.

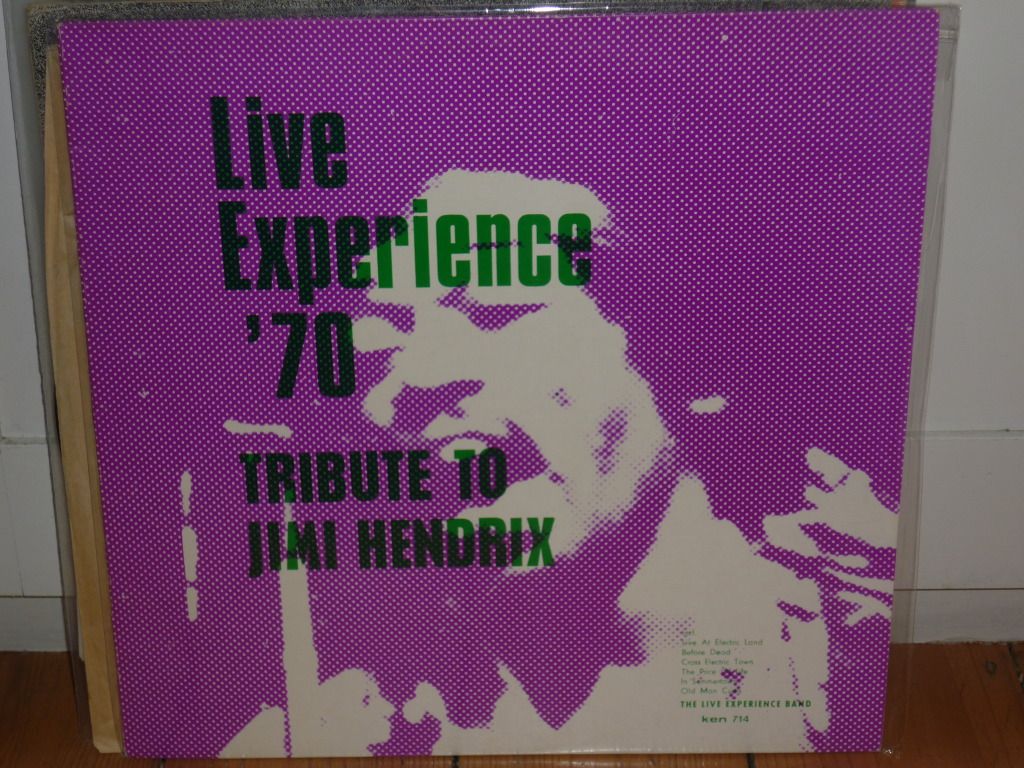

Sure, there's the Hendrix connection - but you could have guessed that by the name of the band. Is the Experience Live or the is the Band Live?

Hendrix is the way into the madness. The work of the world-famous, and as at the time of the release of these records, recently dead, guitar-slinger is just a leaping off point.

Sure they cover the great man's songs, sure they want to sound like him and sometime achieve a quite reasonable facsimile, sure the records are marketed to trap unsuspecting Hendrix fans.

Having died young, and leaving behind a small and confused legacy of recordings, the world in the late sixties and early seventies was crying out for more of the good stuff. You know, the stuff that people loved about Hendrix - the controlled feedback, the guitar pyrotechnics (who else can set his axe on fire and still be cool?), the hard rock and crunching blues.

But there are plenty of records of people trying to sound like Hendrix. And plenty of records of people covering his songs (read about some of them here).

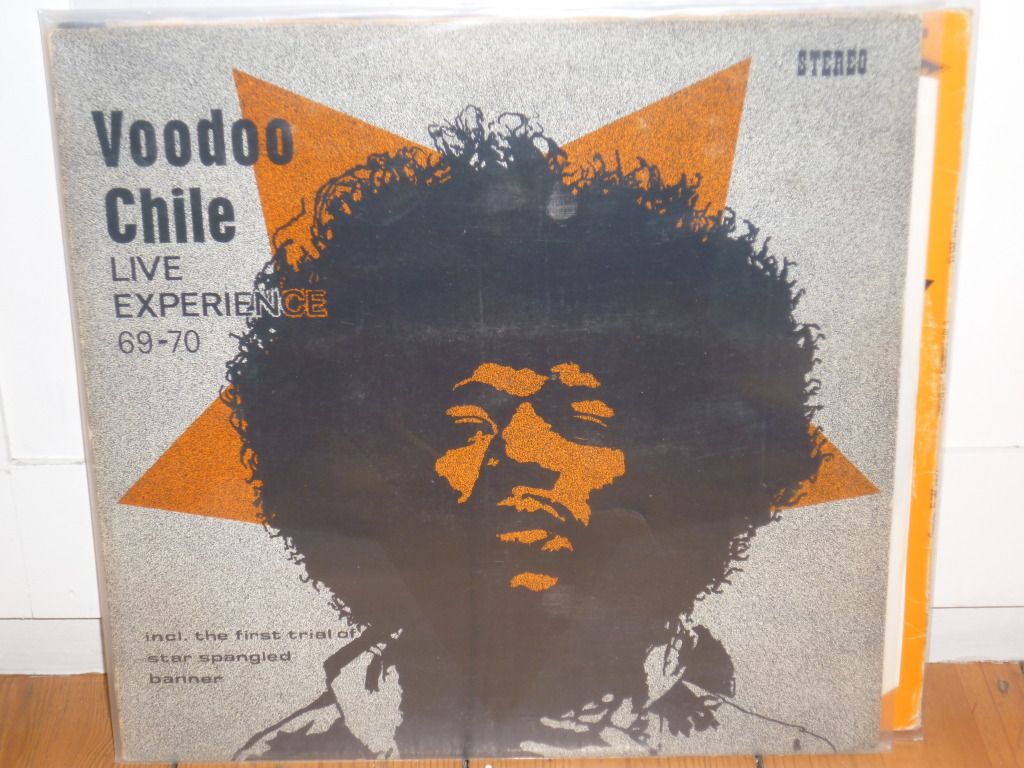

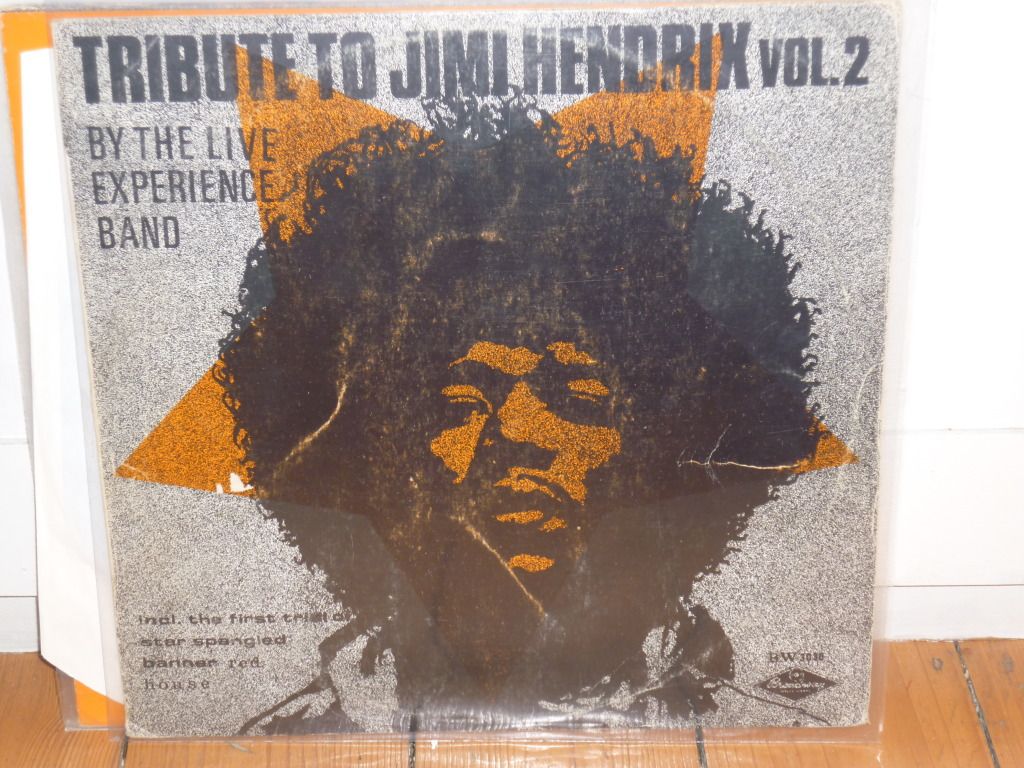

That's not what makes the Live Experience Band's records worth tracking down. Yeah, they tackle some of his well know stuff. Voodoo Chile, Hey Joe, Red House, Purple Haze, all appear. It's not really important to analyse which record includes which version. All we need to know is that it's the same band on every record, pumping out the same vibe. Of course, given the nature of these records, its inevitable that the same performances of the same songs appear on different records. What else did you expect?

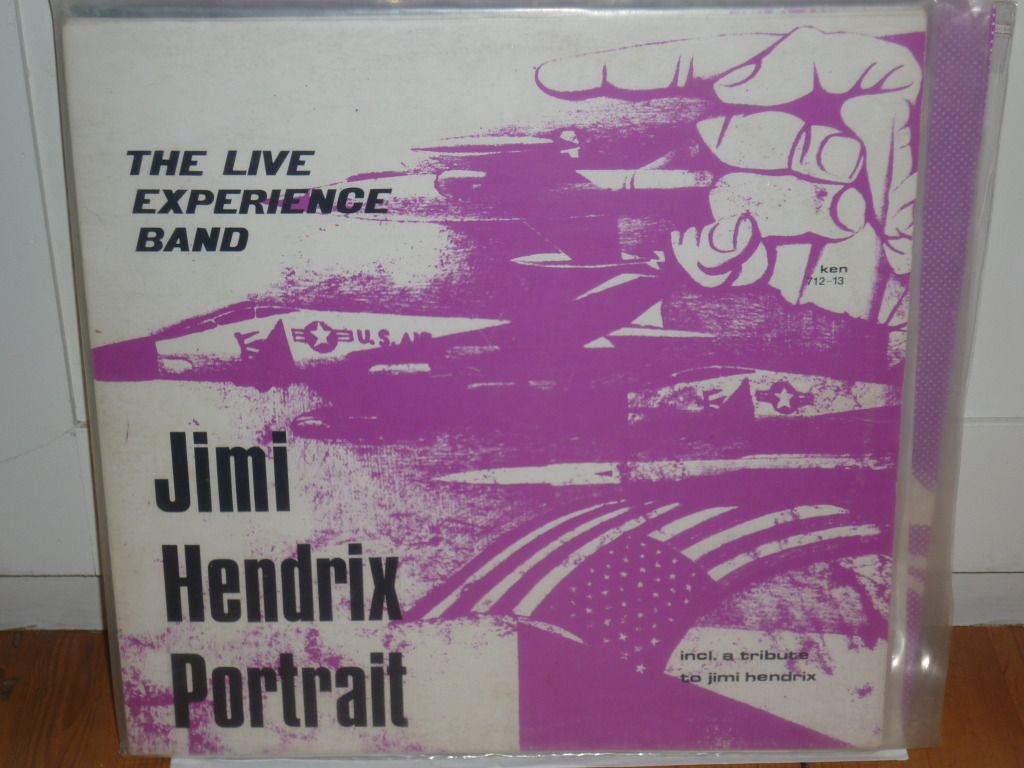

Don't spend too long on the cover versions. Instead revel in the originals, let yourself dive into the ocean of fuzz and feedback. The musicians on these records, allegedly a German band from Hamburg, used Hendrix as a leaping off point, an excuse, a reason to go further, harder, deeper, fuzzier into the realms of the free. To explore some of the territory that Hendrix hinted at through his music and others thought they heard.

Its still hard rock, still blues-based but it contains a wild abandon that for whatever reason, Hendrix just didn't get into his music. Of course, there is none of the genius, none of the boundary challenging approach, nor even the musicianship. What you get is just a balls-out, devil-take-the-hindmost, inspired guitar freakathon. If you want something high-brow, look away now.

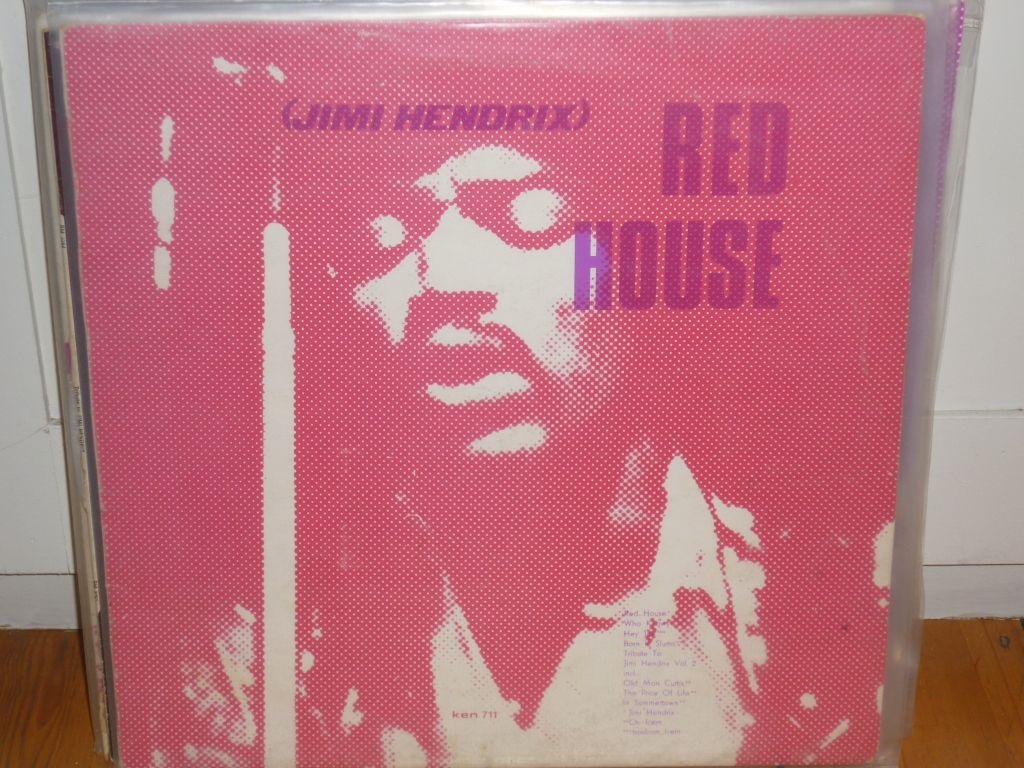

For my money, and lets face it I've bought all of these records, this is the one to aim for.

That's not because it has the best performances, although in places the music is transcendent, but because all of the songs are originals. Whoever 'Icem' is, he certainly could channel the muse of Hendrix.

You could see this as a final squeeze of the sessions that produced these pieces of vinyl. Or you could see this as the triple distilled, 100% proof Live Experience Band. Shorn of attempts to recreate Hendrix's efforts the faintly anonymous Icem lets rip.

What you are presented with are a set of songs that are wilder and more intense than anything Hendrix recorded. Its the kind of music that you wish was used in a biker movie, the kind of music that you know would soundtrack some wild drug-fuelled orgy, the kind of music that long-haired dope-smoking hippies listened to while having tantric sex. Or alternatively the kind music that middle class teenagers listened to because they couldn't get any sex or drugs. You decide.

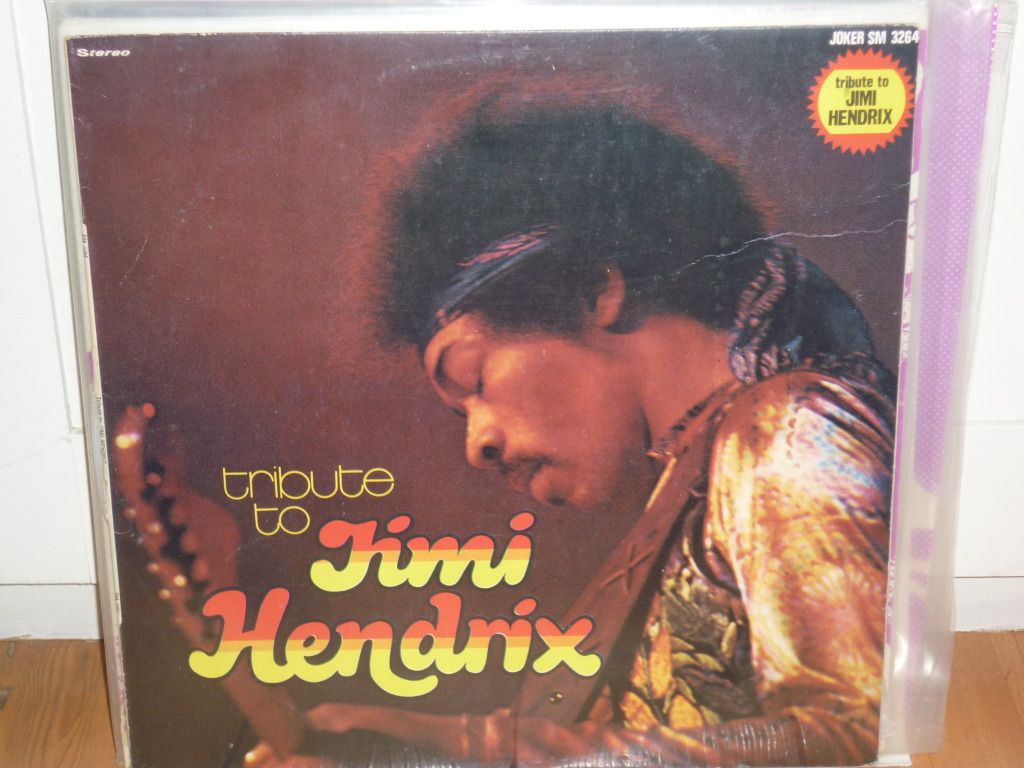

Despite being attributed to Peet Shaw, this record includes music that came from the same sessions that produced the above records.

Repackaged for the Italian market, this one adds some vocals which suddenly brings the way-out music back to earth with a bump.

There is one last record from the same people, although it doesn't purport to be Hendrix related. Its called Blues Happening but, after pummelling my mind with hours of axe-wielding, face-melting, fuzz-busting, free-from, I just don't think I can take any more.

The things I do for this blog! Its not all soft jazz and biscuits I can tell you.

Sometimes you have to suffer a bit, to put yourself through something that you otherwise might not do.

How else can I explain the fact that I've just sat through six whole records of wild, ear-busting, fuzz drenched, screaming, gut-bucket, primal, fuzzed out, no-holds-barred, crazed, derivative, unleashed, fuzz-monster, insane, guitar madness, grimy, gritty, fuzzy (have I already used that word?) Hendrixploitation. This music is so out there that at times it almost feels like free-jazz - there's a point and a melody but you don't always know it. My God, its the kind of music that can only be made by people who either want to break boundaries or who don't know that there are any boundaries in the first place.

Sure, there's the Hendrix connection - but you could have guessed that by the name of the band. Is the Experience Live or the is the Band Live?

Hendrix is the way into the madness. The work of the world-famous, and as at the time of the release of these records, recently dead, guitar-slinger is just a leaping off point.

Sure they cover the great man's songs, sure they want to sound like him and sometime achieve a quite reasonable facsimile, sure the records are marketed to trap unsuspecting Hendrix fans.

Having died young, and leaving behind a small and confused legacy of recordings, the world in the late sixties and early seventies was crying out for more of the good stuff. You know, the stuff that people loved about Hendrix - the controlled feedback, the guitar pyrotechnics (who else can set his axe on fire and still be cool?), the hard rock and crunching blues.

But there are plenty of records of people trying to sound like Hendrix. And plenty of records of people covering his songs (read about some of them here).

That's not what makes the Live Experience Band's records worth tracking down. Yeah, they tackle some of his well know stuff. Voodoo Chile, Hey Joe, Red House, Purple Haze, all appear. It's not really important to analyse which record includes which version. All we need to know is that it's the same band on every record, pumping out the same vibe. Of course, given the nature of these records, its inevitable that the same performances of the same songs appear on different records. What else did you expect?

Don't spend too long on the cover versions. Instead revel in the originals, let yourself dive into the ocean of fuzz and feedback. The musicians on these records, allegedly a German band from Hamburg, used Hendrix as a leaping off point, an excuse, a reason to go further, harder, deeper, fuzzier into the realms of the free. To explore some of the territory that Hendrix hinted at through his music and others thought they heard.

Its still hard rock, still blues-based but it contains a wild abandon that for whatever reason, Hendrix just didn't get into his music. Of course, there is none of the genius, none of the boundary challenging approach, nor even the musicianship. What you get is just a balls-out, devil-take-the-hindmost, inspired guitar freakathon. If you want something high-brow, look away now.

For my money, and lets face it I've bought all of these records, this is the one to aim for.

That's not because it has the best performances, although in places the music is transcendent, but because all of the songs are originals. Whoever 'Icem' is, he certainly could channel the muse of Hendrix.

You could see this as a final squeeze of the sessions that produced these pieces of vinyl. Or you could see this as the triple distilled, 100% proof Live Experience Band. Shorn of attempts to recreate Hendrix's efforts the faintly anonymous Icem lets rip.

What you are presented with are a set of songs that are wilder and more intense than anything Hendrix recorded. Its the kind of music that you wish was used in a biker movie, the kind of music that you know would soundtrack some wild drug-fuelled orgy, the kind of music that long-haired dope-smoking hippies listened to while having tantric sex. Or alternatively the kind music that middle class teenagers listened to because they couldn't get any sex or drugs. You decide.

Despite being attributed to Peet Shaw, this record includes music that came from the same sessions that produced the above records.

Repackaged for the Italian market, this one adds some vocals which suddenly brings the way-out music back to earth with a bump.

There is one last record from the same people, although it doesn't purport to be Hendrix related. Its called Blues Happening but, after pummelling my mind with hours of axe-wielding, face-melting, fuzz-busting, free-from, I just don't think I can take any more.